When Fruit Became Weaponized: A Look at the History of Watermelon in Black America

The first known image associating Black people with watermelons, published in Frank Leslie's Illustrated Newspaper in 1869.

In the years immediately following the Civil War, watermelon farming represented something revolutionary for formerly enslaved people: genuine economic self-determination. After emancipation, when most Black people living in rural areas of the South were left without land and forced to work as laborers on large white-owned farms and plantations, growing and selling watermelons offered a path to independence.

The choice wasn’t arbitrary. Watermelons were relatively easy to grow, didn’t require expensive equipment or large amounts of land, and could be sold roadside or at local markets. For people who had been denied the right to own property or profit from their labor, watermelon farming represented the exercise of fundamental freedoms that had been impossible under slavery. While the gateway to business funding and the halls of academia were non-existent for Blacks, watermelons were a profitable investment used to financially support their families. Thus, it became the symbol of Black freedom in America. However, the success and self-sufficiency of freed Black people challenged the wrong assumptions about Black capabilities many white southerners wanted to hold on to. In response, the racist watermelon stereotype was born.

The Strategic Weaponization During Reconstruction

The transformation of watermelon from a symbol of freedom to a racist stereotype was a calculated response by the established racial hierarchy to depict free Black people as poor, childish, idle, and lazy. The stereotype first arose in the late 1860s, precisely when Reconstruction policies were giving Black Americans political power and economic opportunities.

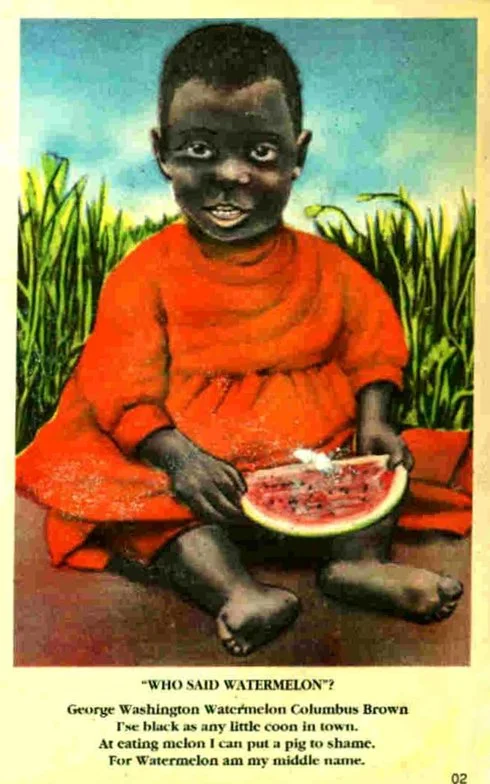

Early-1900s caricature depicting a black child eating a watermelon. Black children at this time were also referred to as “pickaninnies.” (This slur is also used against the aboriginal children of Americas, Australia, and New Zealand.)

During the early 1900s, postcards often depicted African Americans as animalistic creatures “happy to do nothing but eat watermelon.” These “Coon cards” were part of a broader dehumanization campaign that appeared in minstrel shows, advertisements, and popular media. The racist imagery became pervasive, painting Black people as lazy, messy, and simple-minded—a direct contradiction of reality.

The Broader Context of Systematic Oppression

The watermelon stereotype was just one tool in a comprehensive effort to undermine Reconstruction and restore the previous racial order. Those opposed to civil rights gains needed to justify the rollback of these advances and the establishment of Jim Crow laws. By taking symbols of Black success and twisting them into marks of supposed inferiority, they created narratives that would support renewed oppression.

This pattern—taking Black achievements and reframing them as evidence of inferiority—was used across many aspects of life during this period. The nature of this cultural attack worked hand in hand with legal and economic oppression to dismantle the brief promise of Reconstruction.

Reclaiming the True History

Today, scholars, artists, and cultural historians are working to reclaim and restore the authentic history of watermelon as a symbol of Black freedom and entrepreneurship. Museums like the Jim Crow Museum at Ferris State University maintain collections that show both the racist imagery and the historical context, helping people understand how the stereotype was constructed. Contemporary artists are also deliberately incorporating watermelon imagery into their work as acts of resistance. Aaron F. Henderson’s recent work features a well-dressed man holding a watermelon as a symbol of reclaiming cultural identity, directly confronting racist stereotypes that have persisted for generations. This tradition actually has deep roots. Charles Ethan Porter, one of the first African American artists to exhibit nationally, painted dignified watermelon still lifes in the late 1800s, asserting the fruit’s beauty and worth even as racist caricatures proliferated.

Untitled (Cracked Watermelon) by Charles Ethan Porter, c. 1890, oil on canvas, Metropolitan Museum of Art

It’s So Much More Than Fruit

Those of us far who belive we are far removed from the trauma of Jim Crow may dismiss the narrative of watermelon’s past. But we shouldn’t be so quick to do so. Its story in Black America reveals how symbols can be weaponized as tools of oppression, and reclaiming it gives us the opportunity to once again take pride on our achievements as an overcoming people. We can see the watermelon farmers of Reconstruction as the genius agents of their own liberation who used agriculture as a tool of economic independence and self-determination. This stance honors their memory and gives us the continued strength needed to teach the next generation.

SOURCES

Black, Bill. “How Watermelons Became a Racist Trope.” Bunk History, 2017, www.bunkhistory.org/resources/how-watermelons-became-a-racist-trope. Accessed 11 Aug. 2025.

Black, William R. "How Watermelons Became Black: Emancipation and the Origins of a Racist Trope." The Journal of the Civil War Era, vol. 8 no. 1, 2018, p. 64-86. Project MUSE, https://dx.doi.org/10.1353/cwe.2018.0003.

Contributors. “Racist Stereotype of African American People.” Wikipedia.org, Wikimedia Foundation, Inc., 30 Mar. 2013, en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Watermelon_stereotype. Accessed 11 Aug. 2025.

Love, David A. “For Black Americans and Palestinians, Watermelon Has a Special Symbolism.” TheGrio, 22 Nov. 2023, thegrio.com/2023/11/22/for-black-americans-and-palestinians-watermelon-has-a-special-symbolism/. Accessed 11 Aug. 2025.

“Love of Watermelon.” The Stereotype Project Foundation, www.thestereotypeproject.org/sdb/example.

Pages, The Society. “Watermelon: Symbolizing the Supposed Simplicity of Slaves - Sociological Images.” The Society Pages, thesocietypages.org/socimages/2012/12/26/slavery-and-the-watermelon/.

Smithsonian. “Popular and Pervasive Stereotypes of African Americans | National Museum of African American History and Culture.” Nmaahc.si.edu, Smithsonian, 23 Oct. 2018, nmaahc.si.edu/explore/stories/popular-and-pervasive-stereotypes-african-americans.

Wiltz, Dr Allison. “How Watermelon Became a Powerful Symbol of Racism, but Also Resistance.” Medium, 10 Nov. 2023, allyfromnola.medium.com/how-watermelon-became-a-powerful-symbol-of-racism-but-also-resistance-e898203e9011.